On the cusp of 2022, we're still feeling the effects of 2020. But in 2021, at least in terms of books, that was mainly a good thing. Because many 2020 releases were delayed due to the pandemic, 2021 was quite the embarrassment of riches for new novels. Every week, as we put out the new releases at RoscoeBooks, we were astounded at not just the number of new releases, but the number of big-name authors (especially this fall) who published books this year. It was truly an amazing book year.

Even so, I actually read less this year than any in the last 10 or so (around 60 total books and about 23,000 pages). I'm not sure why, it just happened that way. But I still read a ton of amazing books. And actually posted here more than any year since 2015. So that's a plus!

And but so, here are my top 10 favorite books of the year. These are in no particular order, except for No. 1. Since I read it this summer, Damnation Spring has been my no-hesitation answer for favorite book of the year. And it still is.

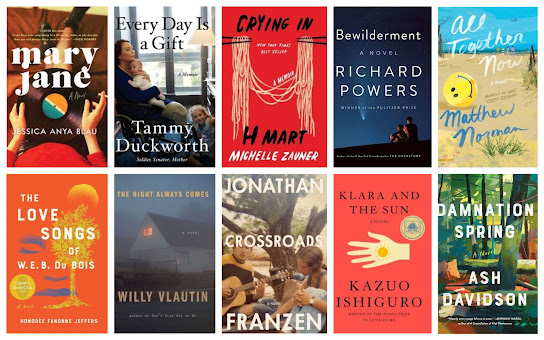

10. Mary Jane, by Jessica Anya Blau — Rock stars: They're just like us. Only waaaaaay cooler. Of any novel I read this year, I think this one surprised me most for how much I loved it. Yes, the "Almost Famous" comparisons are apt, but that's only one of about 10 reasons this novel is fantastic. One of my favorite parts of this novel is the coming-of-age aspect: How Mary Jane reacts when she collides with new ideas and new ways of thinking.

9. Every Day Is A Gift, by Tammy Duckworth — If you thought a memoir about a woman losing her legs in a helicopter crash couldn't also be freakin' hilarious, well, then please meet Tammy Duckworth. I was a huge fan of hers before, but after reading this, I'm in total awe of her. Truly inspirational! And she'll be the first to tell you, she has a lot of work left to do.

8. Crying In H Mart, by Michelle Zauner — This is the second year in a row I've had a musician's memoir in my top 10 (last year was Mikel Jollet's Hollywood Park), and in both cases, the book itself was barely about music. Zauner writes about her often fraught relationship with her mother, her Korean heritage and her attempt to reconnect with it through food, and her grief from her mother's death. Her prose here is clear, precise, and powerful. I fancy myself pretty knowledgable about music, but I had never heard of Japanese Breakfast before reading this memoir. Do yourself a favor, and check out the band's most recent album, which is sort of a companion to this book — it's really great, and of course this book is, too.

7. Bewilderment, by Richard Powers — This novel has more than a little in common with No. 1 on my list, and continues a recent trend in publishing, which I am completely here for: Novels with a decidedly environmentalist bent. This story of a father and his son also has a lot in common with No. 2 on my list below: It's a lesson in empathy. Both of these qualities add up to a richly rewarding reading experience, which, if you've read Powers before, you know is par for the course with him.

6. All Together Now, by Matthew Norman — This quintessential summer novel doubles as a near-perfect "old friends reunion" novel. Matthew Norman is a must-read for me whenever he publishes, and thankfully, he writes quickly. This, his fourth novel, is my favorite of his. Jonathan Tropper, my erstwhile favorite "dude lit" writer, hasn't published anything in 10 years (he's busy writing TV), so I'm thankful Norman has stepped in to fill the void. But with this novel, Norman definitely moves beyond the traditional dude lit. This one's got all kind of heart, and more than a few twists and turns.

5. The Love Songs of W.E.B Dubois, by Honoree Fanonne Jeffers — Full disclosure, I'm not yet finished with this 800-page novel. But I'm close enough to the end that I can confidently add it to this list. This is an epic story of a Black girl's coming of age in modern times, and also the fraught history of her family. Populated with several vivid and fascinating characters, this is a brick of a novel that's actually difficult to put down.

4. The Night Always Comes, by Willy Vlautin — Something this short shouldn't be this powerful. It's almost too cliche to describe novels about poverty and drugs as "gritty," but this novel absolutely is. And it has such an air of authenticity. Just blew me away.

3. Crossroads, by Jonathan Franzen — Of course, The Franzen would make the list. But I'm not just fan-boying by myself over here. Many readers I've talked to have lauded this book as a huge step forward for an already incredibly accomplished novelist. And as the first in a trilogy, it's exciting to be able to look forward to seeing these characters again down the road.

2. Klara and the Sun, by Kazuo Ishiguro — What a gift for readers that a current Nobel laureate is still publishing terrific novels. We have so much to learn from Ishiguro's books, and as with all Ishiguro's stories, he uses parable to make complex ideas simpler, but incredibly profound. Here, a robot teaches us a master class in empathy.

1. Damnation Spring, by Ash Davidson —Damn. Damn. Damn. This is sooooo freakin' good. I loved every second I spent with this book, even with some pretty harrowing plot twists. I cared about these characters so much. It's a truly great American novel.